Your cart is currently empty!

Understanding Dental Enamel: A Scientific Overview

Dental enamel, the outermost layer of teeth, is a highly specialized tissue renowned for its durability and strength. Composition and Structure Enamel is composed predominantly of inorganic materials, with hydroxyapatite crystals accounting for approximately 96% of its weight. This crystalline structure imparts exceptional hardness, enabling enamel to withstand the rigorous forces of mastication. The remaining…

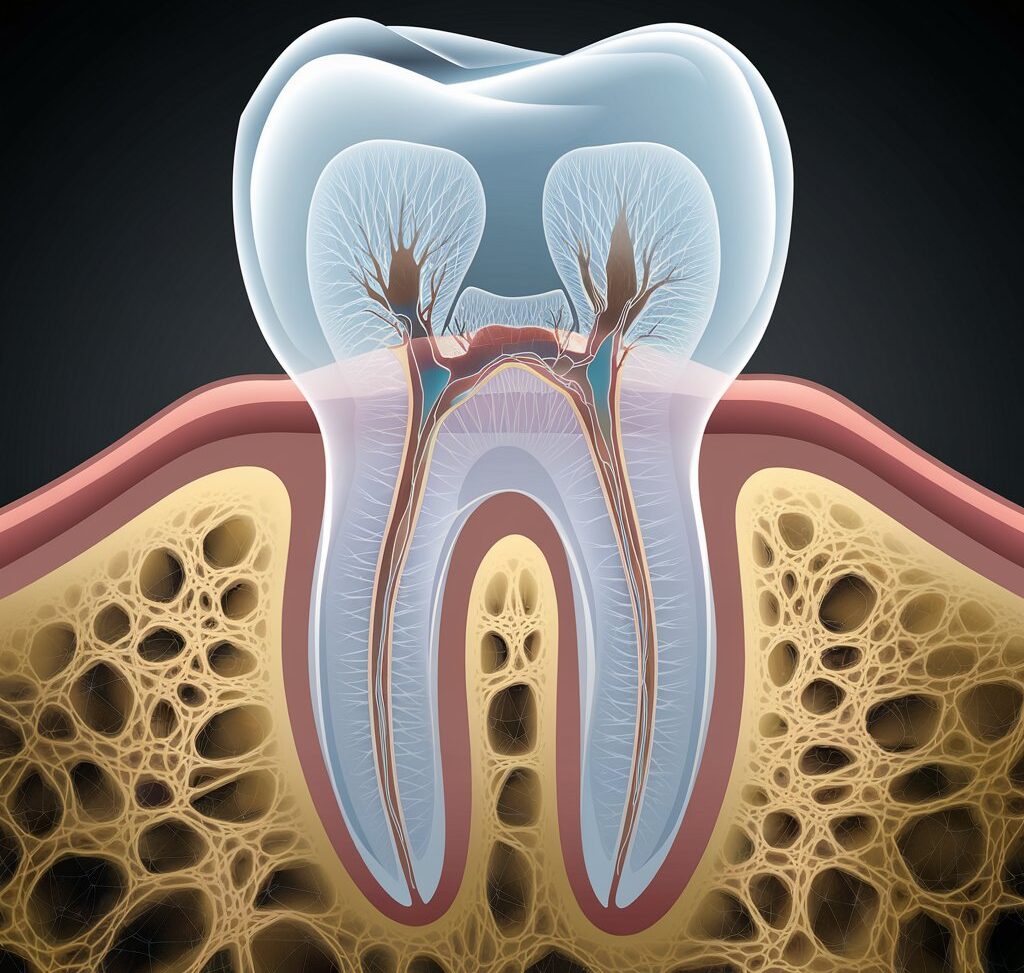

Dental enamel, the outermost layer of teeth, is a highly specialized tissue renowned for its durability and strength.

Composition and Structure

Enamel is composed predominantly of inorganic materials, with hydroxyapatite crystals accounting for approximately 96% of its weight. This crystalline structure imparts exceptional hardness, enabling enamel to withstand the rigorous forces of mastication. The remaining 4% comprises organic material and water, which play a minor role in its mechanical properties but contribute to its ability to resist stress and fracture.

Enamel is organized into tightly packed, rod-shaped structures known as enamel prisms or rods, which extend from the dentino-enamel junction (DEJ) to the enamel surface. These prisms are surrounded by an inter-rod substance, both of which are intricately aligned to maximize structural integrity and resistance to wear. The prism arrangement is unique to each tooth and contributes to its functional adaptability.

Role of Enamel

Enamel serves as a protective barrier for the underlying dentin and pulp, shielding them from physical trauma and bacterial invasion. Additionally, enamel plays a significant role in tooth aesthetics by influencing its color and translucency. Due to its high mineral content, enamel exhibits a glossy appearance that contributes to the natural beauty of a healthy smile.

Despite its remarkable strength, enamel is acellular and lacks the ability to regenerate. Any loss or damage to enamel is permanent, underscoring the importance of its preservation and the prevention of pathological conditions.

Enamel Development (Amelogenesis)

Enamel is formed during the developmental stages of tooth formation in a process known as amelogenesis. This highly regulated process is carried out by ameloblasts, specialized cells that originate from the inner enamel epithelium. Amelogenesis occurs in two primary stages: the secretory phase and the maturation phase.

- Secretory Phase

During the secretory phase, ameloblasts secrete enamel matrix proteins, including amelogenin, ameloblastin, and enamelin. These proteins serve as a scaffold for the initial deposition of hydroxyapatite crystals, forming a soft, partially mineralized matrix. - Maturation Phase

In the maturation phase, the enamel matrix undergoes significant mineralization. Ameloblasts remove organic material and water, allowing the hydroxyapatite crystals to grow in size and density. By the end of this phase, enamel achieves its full hardness and functional capacity.

Once the enamel is fully formed, the ameloblasts disappear, leaving enamel without regenerative potential. This unique characteristic highlights its dependence on external factors for protection and maintenance.

Enamel’s Unique Properties

The exceptional properties of enamel can be attributed to its distinct composition and structural organization:

- Hardness and Wear Resistance: Enamel’s high mineral content makes it the hardest tissue in the body, capable of enduring significant mechanical stress.

- Low Permeability: The tightly packed hydroxyapatite crystals limit the diffusion of substances, protecting the underlying dentin from external chemical and thermal challenges.

- Aesthetic Contribution: Enamel’s translucency and luster enhance the visual appeal of teeth, contributing to a natural and healthy appearance.

Conclusion

Enamel is a remarkable biological material, uniquely designed to protect and enhance the function of teeth. Its intricate structure, coupled with its unparalleled hardness, underscores its critical role in oral health. Understanding the complexities of enamel’s formation, composition, and properties provides a foundation for appreciating its significance in dental anatomy and physiology. This knowledge is essential for advancing the study of oral health and developing effective strategies for maintaining the integrity of this vital tissue.